On Tuesday, 2 April 2024, Politico published the onscreen text WHO pandemic treaty text of Wednesday, 27 March 2024; the time stamp of this 110 page text is 12:44 CET. Article 11 of the proposed agreement contains provisions on transfer of technology and know-how. Nestled within article 11 is paragraph 4bis, the peace clause. The 27 March 2024 pandemic treaty text can be found here: https://keionline.org/misc-docs/who/inb9.wed.27march.pdf

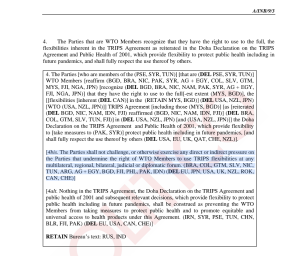

Article 11.4 states:

The Parties that are WTO Members recognize that they have the right to use to the full, the flexibilities inherent in the TRIPS Agreement as reiterated in the Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and Public Health of 2001, which provide flexibility to protect public health including in future pandemics, and shall fully respect the use thereof by others.

Article 11.4bis (the peace clause) states:

[4bis. The Parties shall not challenge, or otherwise exercise any direct or indirect pressure on the Parties that undermine the right of WTO Members to use TRIPS flexibilities at any multilateral, regional, bilateral, judicial or diplomatic forum. (BRA, COL, GTM, SLV, NIC,TUN, ARG, AG + EGY, BGD, FJI, PHL, PAK, IDN) (DEL EU, JPN, USA, UK, NZL, ROK,CAN, CHE)]

A pandemic accord armed with such a peace clause would set an important norm buttressing countries’ sovereign right to use TRIPS flexibilities “at any multilateral, regional, bilateral, judicial or diplomatic forum” without the specter of “direct or indirect pressure”. At the WHO pandemic treaty negotiations, the proponents of the peace clause include: Brazil, Colombia, Guatemala, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Tunisia, Argentina, the African Group + Egypt, Bangladesh, Fiji, Philippines, Pakistan, and Indonesia. The opponents of a peace clause in the WHO Pandemic Accord are: the European Union, Japan, the United States of America, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Canada, and Switzerland.

On Tuesday, 2 April 2024, an informal was convened to resolve the profound differences remaining in Article 11; KEI was informed that Article 11.4bis remained a divisive issue.

Ellen ‘t Hoen, Director of Medicines Law & Policy, provided the following expert insight:

The proposed peace clause in the pandemic accord in fact echoes the basic principle of the WTO TRIPS Agreement. Article 1.1 of the TRIPS Agreement specifies that countries are not obliged to adopt TRIPS-plus measures and “shall be free to determine the appropriate method of implementing the provisions of this Agreement [TRIPS] within their own legal system and practice”. In other words, the proposed peace clause is a welcome reminder of this basic principle, certainly in the context of pandemics.

James Love of KEI made this observation:

In 2001 the WTO Adopted the Doha Declaration on TRIPS and Public Health, and paragraph 4 of that agreement stated that WTO members “should” implement the exceptions in intellectual property laws ” to promote access to medicines for all.” Various versions of this have been adopted in a variety of multilateral, plurilateral and bilateral agreements, but there has persisted enormous pressures on developing countries when they consider actually granting compulsory licenses or using other flexibilities. Here in an agreement dealing with pandemics and emergencies, an agreement motivated in no small part by the inequality of timely access that was a huge feature of the COVID 19 experience,you find several high income countries opposing an agreement to simply honor and give effect to the 2001 WTO agreement on TRIPS and Public Health, and this says volumes about the lack of solidarity and the extent of pharma industry control of the negotiations in those countries.

This is paragraph 4 from the 2001 WTO Doha Declaration on TRIPS and Public Health.

4. We agree that the TRIPS Agreement does not and should not prevent members from taking measures to protect public health. Accordingly, while reiterating our commitment to the TRIPS Agreement, we affirm that the Agreement can and should be interpreted and implemented in a manner supportive of WTO members’ right to protect public health and, in particular, to promote access to medicines for all.

In this connection, we reaffirm the right of WTO members to use, to the full, the provisions in the TRIPS Agreement, which provide flexibility for this purpose.

Luis Villarroel, Director and founder of Innovarte stated:

The “rightly called peace clause” is a proposed solution to the problem of pressures from other countries against developing countries attempting to implement TRIPS flexibilities within their national laws. Such pressures, which also originate from dominant pharmaceutical companies, hinder their capability to adopt flexibilities that are used by developed countries, like the USA. Those are certainly needed for protecting public health in case of a pandemic. The peace clause is a reaffirmation of the principle of sovereignty. It is very discouraging that the European Union, Japan, the United States of America, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Canada, and Switzerland have opposed to such a clause.

KM Gopakumar, Legal Advisor of Third World Network (TWN) observed:

There is well-documented evidence that direct and indirect pressure is used by developed countries and big pharmaceutical corporations to prevent countries from using TRIPS flexibilities, especially government use/compulsory licenses. This proposal makes such coercive activities clearly illegal and allows countries to make use of the TRIPS flexibilities to fulfil. their obligations on the right to health. This is important to facilitate equity.

Brook Baker, Senior Policy Analyst, Health GAP, and Professor Northeastern U. School of Law provided the following comment:

Not only is the idea of a “peace clause” against foreign pressure to restrict adoption, use, and protection of TRIPS flexibilities enshrined in Art. 1.1 of the TRIPS Agreement and in the Doha Declaration, it is absolutely an essential element of a meaningful Pandemic Treaty. The proposed “peace clause” would free countries from the fear of retaliation if and when they take appropriate measures to ensure timely, adequate, and affordable suppliers of pandemic-related health technologies, including from local producers. It is deeply hypocritical for the U.S to oppose a “peace clause” when it issued dozens of contractual, government-use licenses to its suppliers of COVID-19-related health products. It is equally hypocritical of the E.U. to oppose such a guarantee at the same time it is legislating a regional-wide compulsory license system for future pandemic-related health technologies. Likewise, Japan, the U.K., Switzerland, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand also all have compulsory license legislation and would cry bloody murder if any other country challenged their sovereign decision to issue a compulsory license if they were undersupplied in a future pandemic. Why is it too much to ask that there are codified assurances that rich countries will respect a trade-threat ceasefire during future pandemics when countries use lawful TRIPS flexibilities?

Peter Mayburduk, Director of Public Citizen’s Access to Medicines Group observed:

We are disappointed in the Biden administration for failing to support developing country partners in their pursuit of access to medicines for all and the use of health rights consistent with WTO rules. This is an opportunity to show overdue respect and indicate that Washington is open to modest course adjustments in support of a meaningful negotiation. To conclude a meaningful pandemic accord, every country must be prepared to revisit some of its outdated prejudices.

Hu Yuanqiong,PhD, Senior Legal and Policy Advisor for Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) Access Campaign, provided the following response:

Governments of developing countries often face unilateral political pressure when utilising IP flexibilities to address national health needs. For example, the United States Trade Representative’s Special 301 Report consistently criticises the implementation of IP rules and practices promoting access to medical products in various countries. In recent years, in a departure from convention, the report has recognised countries’ right to use compulsory licenses as a public health safeguard to overcome IP barriers on medical products. However, the report continues its public criticism of countries’ use of other TRIPS flexibilities, including stricter patentability criteria to check evergreening, stringent patent examination guidelines and restrictions on data and market exclusivities. Back in 2016, the UN Secretary General’s High Level Panel on Access to Medicines recommended in its report that governments must refrain from explicit or implicit threads, tactics and strategies that undermine the use of TRIPS flexibilities. In light of protecting the right to health as its ultimate objective, the ongoing INB negotiation provides an opportunity to address this long-term issue by explicitly requesting governments to refrain from putting pressures that could undermine the use of TRIPS flexibilities.

Viviana Munoz Tellez, PhD. Coordinator of the Health, Intellectual Property and Biodiversity Programme, South Centre, stressed:

The Peace Clause is necessary. Developed countries and their pharma industry apply undue pressure and threat of litigation to keep developing countries from adopting pro-public health measures that are compatible with the WTO TRIPS agreement (see SC Research paper 132 by Carlos Correa https://www.southcentre.int/research-paper-132-june-2021/).

Dr. Mohga Kamal-Yanni MPhil. MBE, Senior policy advisor to The People Vaccine Alliance, provided the following insights:

How many times did we hear Northern politicians talk about “Equity and solidarity” during the COVID crisis? Yet they acted for inequity and disunity. They protected only their citizens and the profiteering of pharmaceutical companies, at the expense of the rest of the world. The South was forced into a COVID vaccine apartheid.

The Pandemic Accord offers an opportunity to protect every human being, irrespective of who they are and where they are. To do so, it must include solid commitments for technology transfer and removing intellectual property barriers. Unsurprisingly however, rich Northern countries are continuing to refuse to act and are instead committed to protecting pharmaceutical companies’ monopoly power to decide on production, allocation, and price of key lifesaving medical technologies for potential pandemics.

Northern refusal to include a clause that reaffirms what the South already has as a right under the TRIPS agreement, is another glaring example of Northern disregard of people in the South. If they do not agree, then Southern countries must disregard northern pressure and move together to use the TRIPS flexibilities without waiting for approval from pharmaceutical companies or Northern countries. It is time for the South to recognise its power and for the North to realise that medical technology is a global public good that should benefit all that need it.

I hope that the North stops talking about equity because as the Egyptian saying goes: “I hear what you say, I believe you, but I see what you do and I am puzzled”.

Patrick Durisch, health policy expert at Public Eye, commented:

It is appalling that Switzerland opposes a clause already enshrined in a 2001 WTO Agreement on TRIPS and Public Health, even more so in a negotiation over a pandemic accord. For Switzerland and its pharma industry, dealing with pandemics and emergencies is like “business as usual”. The Swiss government already exercised undue political pressure in the past during episodes of compulsory licenses involving Swiss pharma companies in Colombia and Thailand, and it is constantly trying to undermine TRIPS flexibilities through bilateral free trade agreements such as in the recent EFTA-India trade deal. Switzerland should stop overprotecting its pharma industry and instead focus on equity and protect the right to health.

Jaume Vidal, Senior Policy Advisor at Health Action International (HAI) provided the following response:

The so-called peace clause is not only symbolic; it goes to the very root of an effective and equitable response to pandemics beyond legal and regulatory constraints. The opposition by the EU and others to explicitly forbid reprisals against governments because of health-related measures is ominous and concerning; it should be redirected in order to uphold European values of equity, solidarity, as well to respect and promote fundamental human rights to life, health and human dignity.

Piotr Kolczyński, EU Health Policy & Advocacy Advisor for Oxfam commented:

While TRIPS flexibilities may look equal on paper for all WTO members, the imbalance of power in global trade and IP rights’ ownership makes their practical application by higher- and lower-income countries incomparable. Decades of experience show that lower-income countries using flexibilities, such as compulsory licenses, face huge commercial and political pressure or even threats of trade sanctions not to do so.

The WHO Parties’ commitment in the Pandemic Accord not to in any way obstruct or seek to dissuade others from making full use of existing flexibilities could significantly improve the practical ability to exercise these rights in the global South.

Ella Weggen, Senior Global Health Advocate, Wemos provided these insights:

The Peace Clause is nothing new, because it recognises the right to use existing TRIPS flexibilities. But it is very necessary to prevent countries from blocking the use. It underlines the legal possibilities that countries have, to use TRIPS flexibilities. It is disappointing that Northern countries oppose this, especially the EU. During the Covid-19 pandemic, several (EU) countries underlined the importance of global access to Covid-19 innovations. The EU opposed the so-called TRIPS waiver, but instead several countries, like the Netherlands, indicated the importance of the already existing TRIPS flexibilities and the need for facilitating their use. The Peace Clause that is being negotiated as part of the Pandemic Accord would underline this. It is appalling that the EU is opposing it, which shows how powerful the lobby of pharmaceutical companies is.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, Wemos advocated strongly for the sharing of intellectual property, knowledge and data, but this did not happen voluntarily on a large scale. Governments should have the ability to impose measures when their public health is threatened, and the use of TRIPS flexibilities makes that possible. The peace clause therefore seems like a no-brainer. So why are so many rich countries reluctant? Protection of profits over public health? History will repeat itself again and again, looking at the inequality of access in the time of Covid, if we do not change the status quo and facilitate the use of TRIPS flexibilities.

Vanessa López, Executive Director of Salud por Derecho, offered these comments:

Agreed in 2001 and part of the TRIPS agreement, the peace clause is out of the question and its presence in the Pandemic Accord a guarantee of equity and solidarity. Hence, the position of northern countries against the use of flexibilities shows once more the little learned during the COVID crisis. It is very disappointing to see the EU opposing these basic instruments which could contribute to better access to health technologies to low- and middle-income countries, while the region is reviewing its current legislation and mechanisms to reload for future health public crises. The vision of business as usual has no place in the Pandemic Accord since we have seen the consequences. This must be the cornerstone of this accord.

Christopher Baguma, Director of Programs at Ahaki, expressed these observations:

Amidst the chaos of global health crises, the peace clause in the WHO Pandemic Treaty negotiations stands as a beacon of stability, ensuring equitable access to essential medicines and healthcare resources for all nations, regardless of their economic status or geopolitical power.

The Peace Clause is an opportunity to further clarify the use of intellectual property flexibilities, especially during pandemics. By ratifying the use of TRIPS flexibilities during public health emergencies while recognizing the import of opposition, the challenges that have for long been faced by developing countries in utilizing the flexibilities would be minimized. Moreover, ratification of such a clause is fully aligned with public health considerations, as prioritized by the WTO TRIPS Agreement and the Doha Declaration on the TRIPS Agreement and public health.